Androgenetic alopecia (AGA)commonly known as male-pattern or female-pattern hair loss is more than just a cosmetic concern. It is a complex condition influenced by both genetic factors and hormonal activity, and its impact can extend beyond appearance, often affecting emotional well-being and quality of life.

The Genetic Blueprint: Why AGA Runs in Families

One of the most important clues in understanding AGA is its familial pattern. Studies show that AGA follows a polygenic inheritance, meaning it is influenced by multiple genes rather than a single mutation. Among the most studied genes are:

- The androgen receptor (AR) gene, which plays a central role in how hair follicles respond to androgens like testosterone.

- The 5α-reductase gene, which codes for an enzyme that converts testosterone into its more potent form, dihydrotestosterone (DHT).

- Unidentified genetic regions on chromosomes 3 and 21, which have also been linked to early-onset balding.

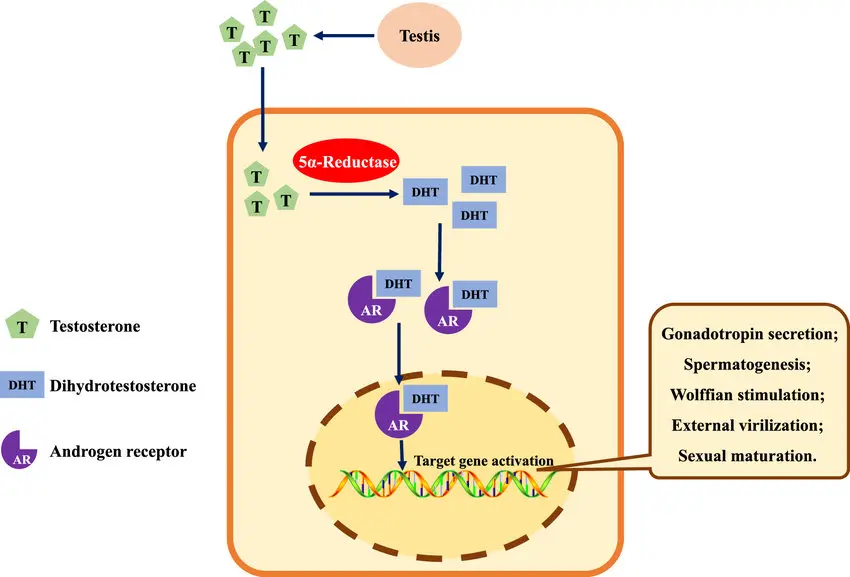

Hormones in Action: Testosterone and DHT

Hormones especially androgens are key drivers of AGA. Testosterone enters the hair follicle through blood vessels in the dermal papilla, where it is converted to DHT by the enzyme 5α-reductase type II.

DHT is significantly more potent than testosterone and binds strongly to androgen receptors in hair follicle cells. This binding leads to:

- Miniaturization of hair follicles

- Shortening of the hair growth cycle

- Thinner, shorter, and less pigmented hair strands

Clinical Patterns: Different in Men and Women

AGA manifests differently between the sexes:

- In men, hair loss typically follows a Hamilton-Norwood pattern, starting at the temples and crown and potentially progressing to full baldness.

-

In women, the hairline is often preserved. Thinning occurs over the crown and central scalp, described by patterns such as:

- Diffuse thinning at the crown with frontal hairline preservation

- Central scalp thinning with widening part

- Thinning with bitemporal recession